Renters' Rights Act: understanding key elements and what it means for the private rented sector

Data Insights

Published by

PriceHubble

-

22 Dec 2025

Renters' Rights Act: understanding key elements and what it means for the private rented sector

Data Insights

Published by

PriceHubble

-

22 Dec 2025

Renters' Rights Act: understanding key elements and what it means for the private rented sector

Data Insights

Published by

PriceHubble

-

22 Dec 2025

The Renters’ Rights Act represents the most significant reform of the private rented sector (PRS) in more than a decade. Among other aspects, it reshapes tenancy agreements, the length of tenure, the rent review process, and therefore also the obligations of private landlords and letting agents. This means there are wide-ranging operational impacts for professionals to understand and implement in their business processes.

Set out below are our views on key elements introduced by the Renters Rights Act, how these new laws affect the rental market, and what data can reveal about market behaviour during this transition period.

What the Renters’ Rights Act changes

Key elements of the tenancy reform measures include:

End of fixed-term tenancies

Tenancies will now default to periodic tenancies with no fixed end date, replacing assured shorthold tenancies. This removes the standard six or twelve-month fixed-term structure and replaces it with a rolling arrangement that continues until either party serves notice (tenants will need to give two months' notice and landlords longer). This change alters how landlords can plan for changes of tenancies and the timing of potential void periods.

End of no-fault evictions

Section 21 evictions will be abolished. Landlords will need to rely on revised Section 8 notice possession grounds, which now include more specific timeframes and stronger requirements to demonstrate a legitimate reason for possession. Eviction notice periods vary depending on the grounds, with longer timeframes of several months’ notice for most situations and shorter ones for serious hazards or anti-social behaviour. A key motivation behind these changes is to help prevent homelessness caused by no-fault evictions and to formalise possession proceedings.

Standardisation of rent increases through section 13

All rent increases for existing tenancies must now pass through the Section 13 procedure. Tenants will be able to challenge a proposed rent increase if they believe it exceeds the market rate. Disputes will be decided by the First-tier Tribunal, which will use evidence from local market rent levels to determine the correct market rent. This strengthens rights for private tenants and places market data at the heart of rental decisions.

Ban on bidding wars

Rental bidding will be prohibited. Letting agents and landlords must set a transparent asking rent and cannot invite offers above that level. PriceHubble data shows that in the past, when a market has been running strong and significant demand is evident, rents have often exceeded the asking price.

Limits on rent in advance

The Renters’ Rights Act will restrict the ability of landlords and letting agents to demand large upfront rent payments to secure a tenancy. After a tenancy agreement has been signed, landlords will only be able to require up to one month’s rent before the tenancy begins.

An ombudsman and expanded redress

A private rented sector landlord ombudsman will provide a single point of contact for complaints about private landlords and letting agents. Local councils will have stronger enforcement powers and can issue financial penalties for non-compliance. The scheme will operate alongside a national redress scheme.

The decent homes standard and Awaab’s law

The Act also sets out a longer-term framework for improved housing safety, including the extension of the Decent Homes Standard to the private rented sector for the first time, as well as the future application of Awaab’s Law. These measures will introduce clearer obligations regarding serious hazards under the Housing Act, including legally defined response timeframes. However, they will be implemented on a slower timetable than the core tenancy and rent reforms, following further consultation and secondary legislation.

Together, these changes signal a gradual shift towards stronger tenant protections, greater operational transparency and a more professionalised rental market. The approach will be applied across England, with related but distinct regimes in Wales and Scotland, and enforcement will be coordinated through Communities and Local Government authorities at the local level.

The Renters’ Rights Act represents the most significant reform of the private rented sector (PRS) in more than a decade. Among other aspects, it reshapes tenancy agreements, the length of tenure, the rent review process, and therefore also the obligations of private landlords and letting agents. This means there are wide-ranging operational impacts for professionals to understand and implement in their business processes.

Set out below are our views on key elements introduced by the Renters Rights Act, how these new laws affect the rental market, and what data can reveal about market behaviour during this transition period.

What the Renters’ Rights Act changes

Key elements of the tenancy reform measures include:

End of fixed-term tenancies

Tenancies will now default to periodic tenancies with no fixed end date, replacing assured shorthold tenancies. This removes the standard six or twelve-month fixed-term structure and replaces it with a rolling arrangement that continues until either party serves notice (tenants will need to give two months' notice and landlords longer). This change alters how landlords can plan for changes of tenancies and the timing of potential void periods.

End of no-fault evictions

Section 21 evictions will be abolished. Landlords will need to rely on revised Section 8 notice possession grounds, which now include more specific timeframes and stronger requirements to demonstrate a legitimate reason for possession. Eviction notice periods vary depending on the grounds, with longer timeframes of several months’ notice for most situations and shorter ones for serious hazards or anti-social behaviour. A key motivation behind these changes is to help prevent homelessness caused by no-fault evictions and to formalise possession proceedings.

Standardisation of rent increases through section 13

All rent increases for existing tenancies must now pass through the Section 13 procedure. Tenants will be able to challenge a proposed rent increase if they believe it exceeds the market rate. Disputes will be decided by the First-tier Tribunal, which will use evidence from local market rent levels to determine the correct market rent. This strengthens rights for private tenants and places market data at the heart of rental decisions.

Ban on bidding wars

Rental bidding will be prohibited. Letting agents and landlords must set a transparent asking rent and cannot invite offers above that level. PriceHubble data shows that in the past, when a market has been running strong and significant demand is evident, rents have often exceeded the asking price.

Limits on rent in advance

The Renters’ Rights Act will restrict the ability of landlords and letting agents to demand large upfront rent payments to secure a tenancy. After a tenancy agreement has been signed, landlords will only be able to require up to one month’s rent before the tenancy begins.

An ombudsman and expanded redress

A private rented sector landlord ombudsman will provide a single point of contact for complaints about private landlords and letting agents. Local councils will have stronger enforcement powers and can issue financial penalties for non-compliance. The scheme will operate alongside a national redress scheme.

The decent homes standard and Awaab’s law

The Act also sets out a longer-term framework for improved housing safety, including the extension of the Decent Homes Standard to the private rented sector for the first time, as well as the future application of Awaab’s Law. These measures will introduce clearer obligations regarding serious hazards under the Housing Act, including legally defined response timeframes. However, they will be implemented on a slower timetable than the core tenancy and rent reforms, following further consultation and secondary legislation.

Together, these changes signal a gradual shift towards stronger tenant protections, greater operational transparency and a more professionalised rental market. The approach will be applied across England, with related but distinct regimes in Wales and Scotland, and enforcement will be coordinated through Communities and Local Government authorities at the local level.

The Renters’ Rights Act represents the most significant reform of the private rented sector (PRS) in more than a decade. Among other aspects, it reshapes tenancy agreements, the length of tenure, the rent review process, and therefore also the obligations of private landlords and letting agents. This means there are wide-ranging operational impacts for professionals to understand and implement in their business processes.

Set out below are our views on key elements introduced by the Renters Rights Act, how these new laws affect the rental market, and what data can reveal about market behaviour during this transition period.

What the Renters’ Rights Act changes

Key elements of the tenancy reform measures include:

End of fixed-term tenancies

Tenancies will now default to periodic tenancies with no fixed end date, replacing assured shorthold tenancies. This removes the standard six or twelve-month fixed-term structure and replaces it with a rolling arrangement that continues until either party serves notice (tenants will need to give two months' notice and landlords longer). This change alters how landlords can plan for changes of tenancies and the timing of potential void periods.

End of no-fault evictions

Section 21 evictions will be abolished. Landlords will need to rely on revised Section 8 notice possession grounds, which now include more specific timeframes and stronger requirements to demonstrate a legitimate reason for possession. Eviction notice periods vary depending on the grounds, with longer timeframes of several months’ notice for most situations and shorter ones for serious hazards or anti-social behaviour. A key motivation behind these changes is to help prevent homelessness caused by no-fault evictions and to formalise possession proceedings.

Standardisation of rent increases through section 13

All rent increases for existing tenancies must now pass through the Section 13 procedure. Tenants will be able to challenge a proposed rent increase if they believe it exceeds the market rate. Disputes will be decided by the First-tier Tribunal, which will use evidence from local market rent levels to determine the correct market rent. This strengthens rights for private tenants and places market data at the heart of rental decisions.

Ban on bidding wars

Rental bidding will be prohibited. Letting agents and landlords must set a transparent asking rent and cannot invite offers above that level. PriceHubble data shows that in the past, when a market has been running strong and significant demand is evident, rents have often exceeded the asking price.

Limits on rent in advance

The Renters’ Rights Act will restrict the ability of landlords and letting agents to demand large upfront rent payments to secure a tenancy. After a tenancy agreement has been signed, landlords will only be able to require up to one month’s rent before the tenancy begins.

An ombudsman and expanded redress

A private rented sector landlord ombudsman will provide a single point of contact for complaints about private landlords and letting agents. Local councils will have stronger enforcement powers and can issue financial penalties for non-compliance. The scheme will operate alongside a national redress scheme.

The decent homes standard and Awaab’s law

The Act also sets out a longer-term framework for improved housing safety, including the extension of the Decent Homes Standard to the private rented sector for the first time, as well as the future application of Awaab’s Law. These measures will introduce clearer obligations regarding serious hazards under the Housing Act, including legally defined response timeframes. However, they will be implemented on a slower timetable than the core tenancy and rent reforms, following further consultation and secondary legislation.

Together, these changes signal a gradual shift towards stronger tenant protections, greater operational transparency and a more professionalised rental market. The approach will be applied across England, with related but distinct regimes in Wales and Scotland, and enforcement will be coordinated through Communities and Local Government authorities at the local level.

Research

The UK rental market in 10 charts

Research

The UK rental market in 10 charts

How does the Renters’ Rights Act affect current market behaviour?

Utilising the depth of our rental datasets, we suggest that several trends are likely to emerge as the market moves towards the implementation of the Renters’ Rights Act.

Asking rents may rise slightly

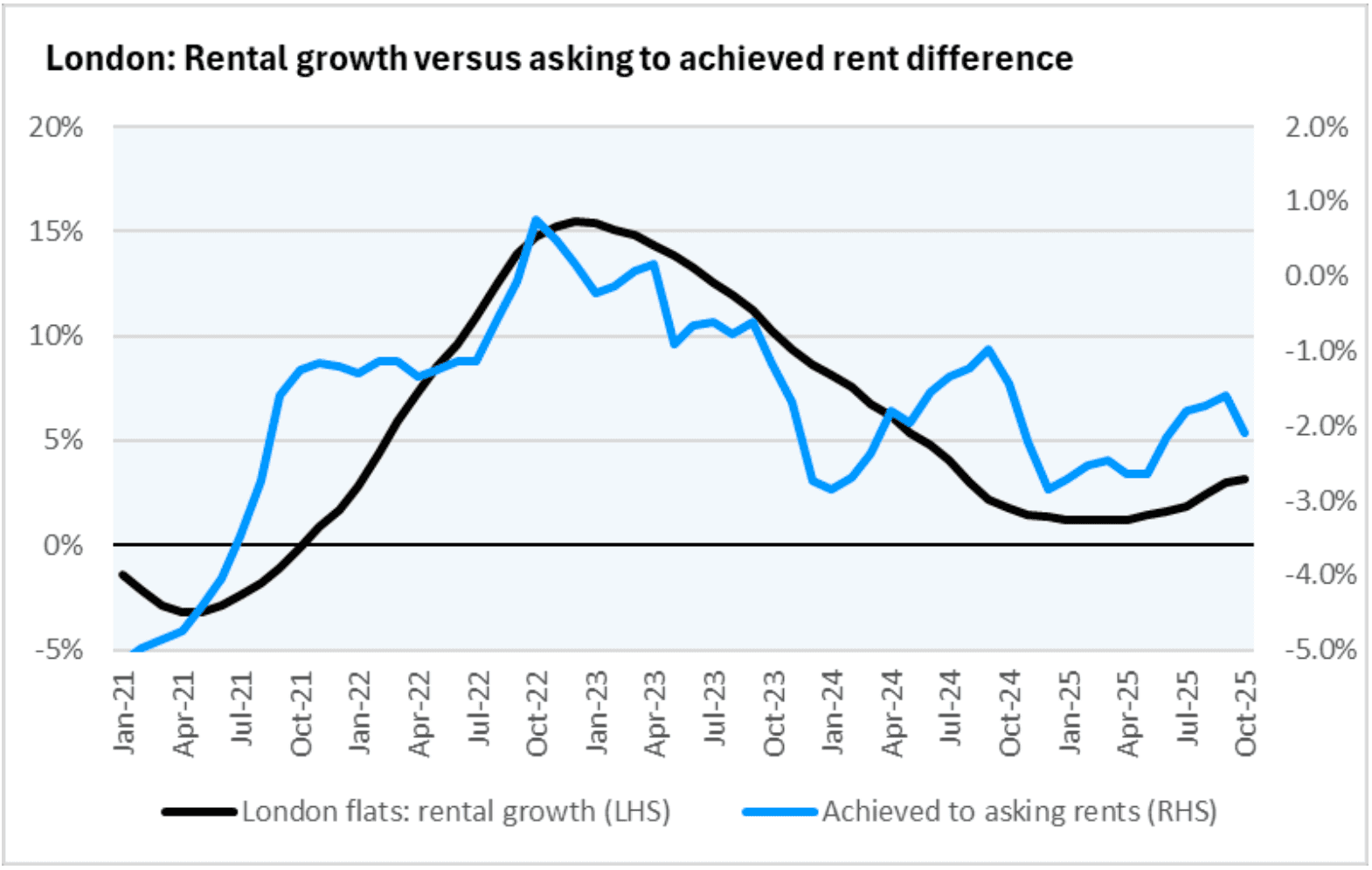

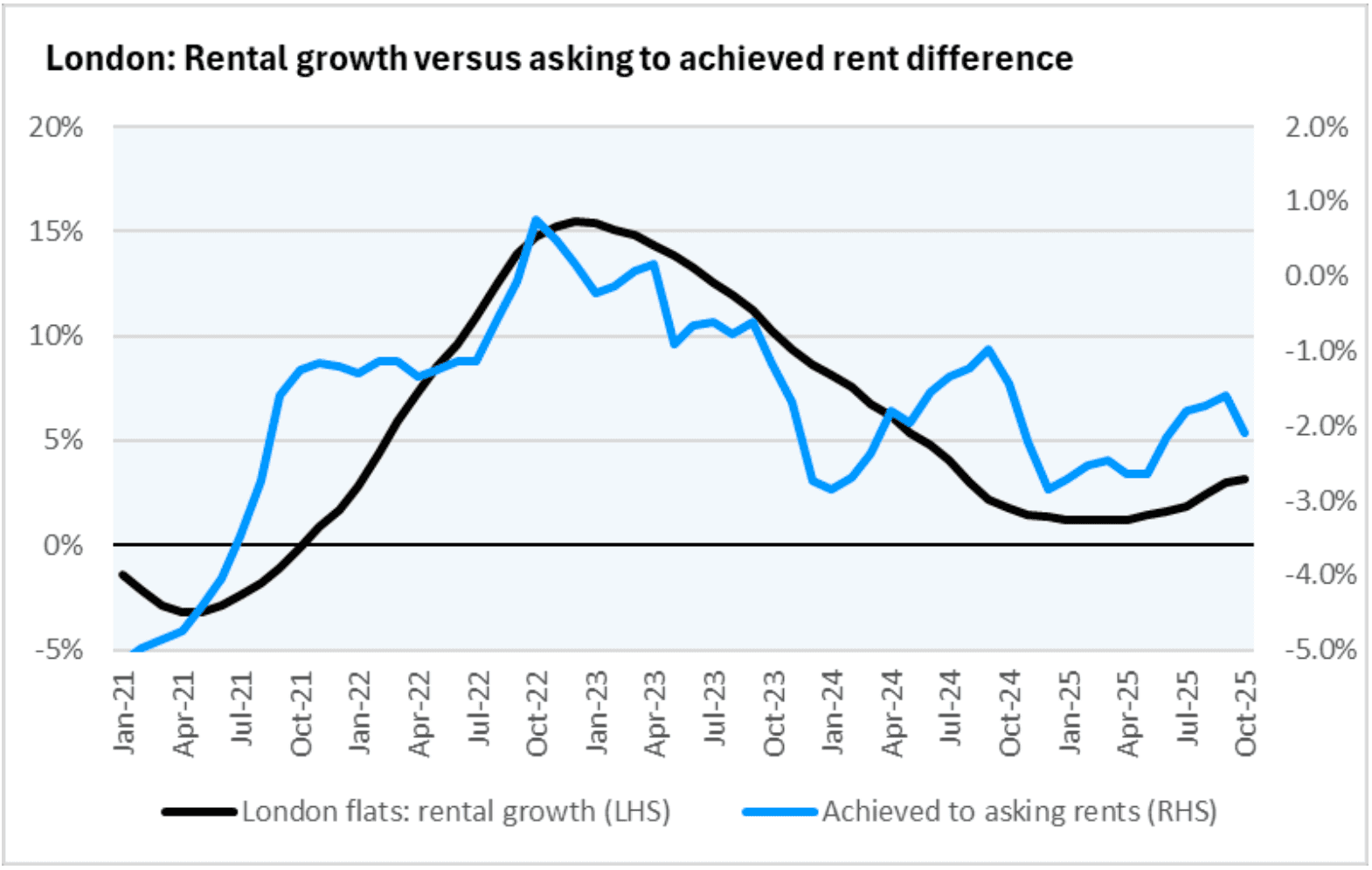

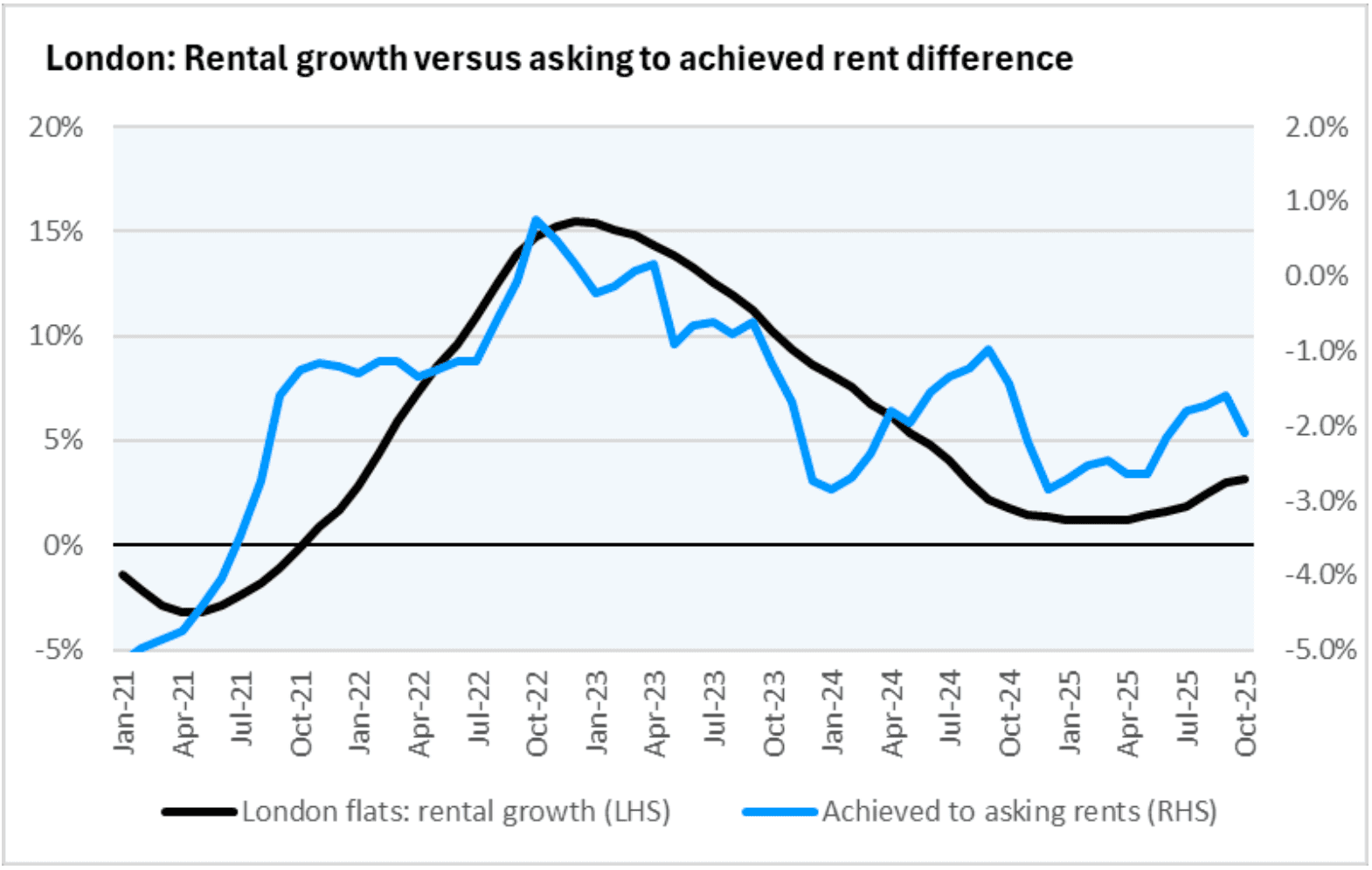

Analysing historic data, we can see that the difference between asking and achieved rents varies through the cycle. It is not a consistent rate through time. This same data shows that when the market is running strong with high levels of renter demand, then there has been a premium on achieved rent over asking.

For example, London data reveals an average discount of 1.8 per cent between listed and achieved rents over the last 5 years. This gap widened when market demand was weak through COVID-19 (at this point, there was over a 5 per cent discount from asking to achieved rents). Then, at the peak of the rental cycle in 2022, as the market recovered, achieved rents ran slightly above asking rents (0.8 per cent).

Related to this, the data also shows that the proportion of properties achieving above-asking rent has varied throughout the cycle. Again, looking at London data, this has averaged one in five tenancies above asking since 2021. When market demand is running strong this has increased to one in three tenancies above asking. With bidding wars prohibited, the likely outcome is that asking rents may rise slightly as landlords adjust to a single transparent price point.

Potential supply pressures in the private rented sector

The Renters’ Rights Act is the latest in a long line of tax and legislative changes affecting landlords. As a consequence, some landlords are selling up, and new investment has been lower. This is evidenced through mortgage data, which shows that Buy-to-Let lending has remained below trend since 2022. Furthermore, most of this lending activity relates to remortgaging rather than the purchase of new properties.

Alongside this, Savills research suggests that around 290,000 rented homes were lost from the private rented sector between 2021 and 2024. The extra compliance burden of the Renters’ Rights Act may reinforce this trend. If further disinvestment materialises in a significant way, then there could well be undersupply pressures in some local markets.

There is, however, an offset to extra compliance and taxation. Recent significant improvement in residential yields and lower mortgage rates could attract some investors back. The market is certainly moving towards a more professional footing with less activity from smaller and so-called accidental landlords (for instance, those who inherited a property). Investment trends do vary by region, with more investor activity in more affordable markets and less activity from investors in London and the South East.

Harder for landlords to justify large rental increases

The Renters' Rights Act will bring everything back to an evidence base for rent levels, making it more difficult for landlords to unjustifiably increase rents for existing tenancies through the annual rent review process (via Section 13).

Why rent evidence has become essential

One of the most immediate operational impacts of the Renters’ Rights Bill is the requirement to evidence rent increases. Under Section 13, every increase must reflect the open market level. Tenants can challenge any increase that appears unsupported. In practice, this likely means landlords and operators, for transparency and best practice, should attach market rent evidence to every Section 13 notice.

This evidence should demonstrate that the proposed rent is aligned with local market rent, taking into account comparable rental properties, recently achieved rents and where this property sits within the range of local rents. It will become part of the standard documentation for new tenancies and for renewals.

PriceHubble’s Market Analyser provides a wealth of this data to support this purpose, including:

Achieved rents, by property type, bedroom count and local area

Annual change in rent paid, showing actual market inflation

The range of local rents within a user-defined geography

Current asking rents

BTR-specific asking rents and premium segment indicators

Regional benchmarks to show broader market patterns

These datasets provide an objective basis for setting, reviewing and communicating rents. They also help form a defensible evidence trail for the First-tier Tribunal if a Section 13 increase is challenged.

What professionals should prepare for

The new regulatory landscape will require a more structured and transparent approach. Key priorities include:

Creating a consistent internal rent setting policy

Documenting comparables, achieved rents and local rent ranges

Monitoring rent arrears and anti-social behaviour incidents in line with the updated possession grounds

Ensuring all tenancy agreements reflect the new periodic structure

Preparing internal workflows for ombudsman and redress processes

Professionals who adopt a data-driven approach will be able to adapt more easily to new expectations and will be better positioned to effectively guide landlords.

Will this alter the outlook for rents?

Over the long term, rents are affected by a multitude of factors and tend to grow in line with earnings. There is no current expectation that this long-term relationship will change with the introduction of the Renters' Rights Act. However, there may be some short-term variation as the private rental sector adjusts to different market conditions and new compliance requirements.

Consensus forecasts currently suggest an average national rental growth of around 3% per annum over the next few years; however, local conditions vary. Where the supply of rental stock remains tight, upward pressure may continue at higher levels than predicted, although the ability to raise rents will also depend on housing affordability.

If landlord participation continues to decline, local authorities and the central government may increase their attention to supply-side pressures. Build-to-rent schemes and professionally managed portfolios will play an increasingly significant role within the sector, both in terms of supply and in leading best practices and regulatory compliance.

The Renters’ Rights Act represents a clear shift towards transparency, stability and increased professionalism. With a robust evidence base, operators can navigate the transition to the new rules with confidence and maintain trust with private tenants, local authorities, and the broader sector.

How does the Renters’ Rights Act affect current market behaviour?

Utilising the depth of our rental datasets, we suggest that several trends are likely to emerge as the market moves towards the implementation of the Renters’ Rights Act.

Asking rents may rise slightly

Analysing historic data, we can see that the difference between asking and achieved rents varies through the cycle. It is not a consistent rate through time. This same data shows that when the market is running strong with high levels of renter demand, then there has been a premium on achieved rent over asking.

For example, London data reveals an average discount of 1.8 per cent between listed and achieved rents over the last 5 years. This gap widened when market demand was weak through COVID-19 (at this point, there was over a 5 per cent discount from asking to achieved rents). Then, at the peak of the rental cycle in 2022, as the market recovered, achieved rents ran slightly above asking rents (0.8 per cent).

Related to this, the data also shows that the proportion of properties achieving above-asking rent has varied throughout the cycle. Again, looking at London data, this has averaged one in five tenancies above asking since 2021. When market demand is running strong this has increased to one in three tenancies above asking. With bidding wars prohibited, the likely outcome is that asking rents may rise slightly as landlords adjust to a single transparent price point.

Potential supply pressures in the private rented sector

The Renters’ Rights Act is the latest in a long line of tax and legislative changes affecting landlords. As a consequence, some landlords are selling up, and new investment has been lower. This is evidenced through mortgage data, which shows that Buy-to-Let lending has remained below trend since 2022. Furthermore, most of this lending activity relates to remortgaging rather than the purchase of new properties.

Alongside this, Savills research suggests that around 290,000 rented homes were lost from the private rented sector between 2021 and 2024. The extra compliance burden of the Renters’ Rights Act may reinforce this trend. If further disinvestment materialises in a significant way, then there could well be undersupply pressures in some local markets.

There is, however, an offset to extra compliance and taxation. Recent significant improvement in residential yields and lower mortgage rates could attract some investors back. The market is certainly moving towards a more professional footing with less activity from smaller and so-called accidental landlords (for instance, those who inherited a property). Investment trends do vary by region, with more investor activity in more affordable markets and less activity from investors in London and the South East.

Harder for landlords to justify large rental increases

The Renters' Rights Act will bring everything back to an evidence base for rent levels, making it more difficult for landlords to unjustifiably increase rents for existing tenancies through the annual rent review process (via Section 13).

Why rent evidence has become essential

One of the most immediate operational impacts of the Renters’ Rights Bill is the requirement to evidence rent increases. Under Section 13, every increase must reflect the open market level. Tenants can challenge any increase that appears unsupported. In practice, this likely means landlords and operators, for transparency and best practice, should attach market rent evidence to every Section 13 notice.

This evidence should demonstrate that the proposed rent is aligned with local market rent, taking into account comparable rental properties, recently achieved rents and where this property sits within the range of local rents. It will become part of the standard documentation for new tenancies and for renewals.

PriceHubble’s Market Analyser provides a wealth of this data to support this purpose, including:

Achieved rents, by property type, bedroom count and local area

Annual change in rent paid, showing actual market inflation

The range of local rents within a user-defined geography

Current asking rents

BTR-specific asking rents and premium segment indicators

Regional benchmarks to show broader market patterns

These datasets provide an objective basis for setting, reviewing and communicating rents. They also help form a defensible evidence trail for the First-tier Tribunal if a Section 13 increase is challenged.

What professionals should prepare for

The new regulatory landscape will require a more structured and transparent approach. Key priorities include:

Creating a consistent internal rent setting policy

Documenting comparables, achieved rents and local rent ranges

Monitoring rent arrears and anti-social behaviour incidents in line with the updated possession grounds

Ensuring all tenancy agreements reflect the new periodic structure

Preparing internal workflows for ombudsman and redress processes

Professionals who adopt a data-driven approach will be able to adapt more easily to new expectations and will be better positioned to effectively guide landlords.

Will this alter the outlook for rents?

Over the long term, rents are affected by a multitude of factors and tend to grow in line with earnings. There is no current expectation that this long-term relationship will change with the introduction of the Renters' Rights Act. However, there may be some short-term variation as the private rental sector adjusts to different market conditions and new compliance requirements.

Consensus forecasts currently suggest an average national rental growth of around 3% per annum over the next few years; however, local conditions vary. Where the supply of rental stock remains tight, upward pressure may continue at higher levels than predicted, although the ability to raise rents will also depend on housing affordability.

If landlord participation continues to decline, local authorities and the central government may increase their attention to supply-side pressures. Build-to-rent schemes and professionally managed portfolios will play an increasingly significant role within the sector, both in terms of supply and in leading best practices and regulatory compliance.

The Renters’ Rights Act represents a clear shift towards transparency, stability and increased professionalism. With a robust evidence base, operators can navigate the transition to the new rules with confidence and maintain trust with private tenants, local authorities, and the broader sector.

How does the Renters’ Rights Act affect current market behaviour?

Utilising the depth of our rental datasets, we suggest that several trends are likely to emerge as the market moves towards the implementation of the Renters’ Rights Act.

Asking rents may rise slightly

Analysing historic data, we can see that the difference between asking and achieved rents varies through the cycle. It is not a consistent rate through time. This same data shows that when the market is running strong with high levels of renter demand, then there has been a premium on achieved rent over asking.

For example, London data reveals an average discount of 1.8 per cent between listed and achieved rents over the last 5 years. This gap widened when market demand was weak through COVID-19 (at this point, there was over a 5 per cent discount from asking to achieved rents). Then, at the peak of the rental cycle in 2022, as the market recovered, achieved rents ran slightly above asking rents (0.8 per cent).

Related to this, the data also shows that the proportion of properties achieving above-asking rent has varied throughout the cycle. Again, looking at London data, this has averaged one in five tenancies above asking since 2021. When market demand is running strong this has increased to one in three tenancies above asking. With bidding wars prohibited, the likely outcome is that asking rents may rise slightly as landlords adjust to a single transparent price point.

Potential supply pressures in the private rented sector

The Renters’ Rights Act is the latest in a long line of tax and legislative changes affecting landlords. As a consequence, some landlords are selling up, and new investment has been lower. This is evidenced through mortgage data, which shows that Buy-to-Let lending has remained below trend since 2022. Furthermore, most of this lending activity relates to remortgaging rather than the purchase of new properties.

Alongside this, Savills research suggests that around 290,000 rented homes were lost from the private rented sector between 2021 and 2024. The extra compliance burden of the Renters’ Rights Act may reinforce this trend. If further disinvestment materialises in a significant way, then there could well be undersupply pressures in some local markets.

There is, however, an offset to extra compliance and taxation. Recent significant improvement in residential yields and lower mortgage rates could attract some investors back. The market is certainly moving towards a more professional footing with less activity from smaller and so-called accidental landlords (for instance, those who inherited a property). Investment trends do vary by region, with more investor activity in more affordable markets and less activity from investors in London and the South East.

Harder for landlords to justify large rental increases

The Renters' Rights Act will bring everything back to an evidence base for rent levels, making it more difficult for landlords to unjustifiably increase rents for existing tenancies through the annual rent review process (via Section 13).

Why rent evidence has become essential

One of the most immediate operational impacts of the Renters’ Rights Bill is the requirement to evidence rent increases. Under Section 13, every increase must reflect the open market level. Tenants can challenge any increase that appears unsupported. In practice, this likely means landlords and operators, for transparency and best practice, should attach market rent evidence to every Section 13 notice.

This evidence should demonstrate that the proposed rent is aligned with local market rent, taking into account comparable rental properties, recently achieved rents and where this property sits within the range of local rents. It will become part of the standard documentation for new tenancies and for renewals.

PriceHubble’s Market Analyser provides a wealth of this data to support this purpose, including:

Achieved rents, by property type, bedroom count and local area

Annual change in rent paid, showing actual market inflation

The range of local rents within a user-defined geography

Current asking rents

BTR-specific asking rents and premium segment indicators

Regional benchmarks to show broader market patterns

These datasets provide an objective basis for setting, reviewing and communicating rents. They also help form a defensible evidence trail for the First-tier Tribunal if a Section 13 increase is challenged.

What professionals should prepare for

The new regulatory landscape will require a more structured and transparent approach. Key priorities include:

Creating a consistent internal rent setting policy

Documenting comparables, achieved rents and local rent ranges

Monitoring rent arrears and anti-social behaviour incidents in line with the updated possession grounds

Ensuring all tenancy agreements reflect the new periodic structure

Preparing internal workflows for ombudsman and redress processes

Professionals who adopt a data-driven approach will be able to adapt more easily to new expectations and will be better positioned to effectively guide landlords.

Will this alter the outlook for rents?

Over the long term, rents are affected by a multitude of factors and tend to grow in line with earnings. There is no current expectation that this long-term relationship will change with the introduction of the Renters' Rights Act. However, there may be some short-term variation as the private rental sector adjusts to different market conditions and new compliance requirements.

Consensus forecasts currently suggest an average national rental growth of around 3% per annum over the next few years; however, local conditions vary. Where the supply of rental stock remains tight, upward pressure may continue at higher levels than predicted, although the ability to raise rents will also depend on housing affordability.

If landlord participation continues to decline, local authorities and the central government may increase their attention to supply-side pressures. Build-to-rent schemes and professionally managed portfolios will play an increasingly significant role within the sector, both in terms of supply and in leading best practices and regulatory compliance.

The Renters’ Rights Act represents a clear shift towards transparency, stability and increased professionalism. With a robust evidence base, operators can navigate the transition to the new rules with confidence and maintain trust with private tenants, local authorities, and the broader sector.

See also

News

Read more →

News

Read more →

News

Read more →

Request a demo

We will get back to you quickly.

We look forward to speaking with you.

Thank you!

We will get back to you within 24 business hours.

Thank you!

We will get back to you within 24 business hours.